LAVEEN, Arizona – The Secretary of the U.S. Interior Deb Haaland leads the Road to Healing Tour into the New Year, making the fourth stop at the Gila River Indian Community on Jan. 20 and Navajo Nation at Many Farms on Jan. 22. The Secretary and Assistant Bryan Newland kicked off the tour from the eldest operating boarding school, Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, Okla. on July 9, 2022.

Multiple stops along the way included Michigan, South Dakota, and Arizona, with more events to come during the year.

“The road to healing will continue through 2023,” Haaland said. “We have more events to do in every part of the United States.”

The tour was launched after the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative released a volume one report written by Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland in May 2022. The report concluded that connecting with the Native communities and gathering their oral stories would be the most beneficial tool for healing and identifying resources the agency will need to continue.

These oral histories will be released as a part of the report’s second volume. “As we keep investigating the federal Indian Boarding School system and learning about the experience in specific schools and the overall system, it paints a history that records alone can’t fully provide,” Newland said.

Newland explained that DOI’s next steps, in addition to collecting oral testimonies, will include identifying unmarked burial sites across the federal Indian Boarding School system and the total amount of funding the federal government put towards erasing Native culture.

Haaland has heard the horrors personally from her grandparents, who were taken from their homelands in Laguna Pueblo, New Mexico, and sent off to boarding schools. As a descendant, she can feel the trauma in herself and the effects that ripple through her family generation after generation.

“My grandmother went to boarding school, and I suffer from intergenerational trauma as much as anybody,” Haaland said during an interview with Native News Online. “So because I understand it, I am going to be understanding to other people.”

So far, the duo has recorded the horrible accounts of those traumatized for a lifetime by the attempted assimilation and dissertation that has been bottled up among tribal members for more than half a century.

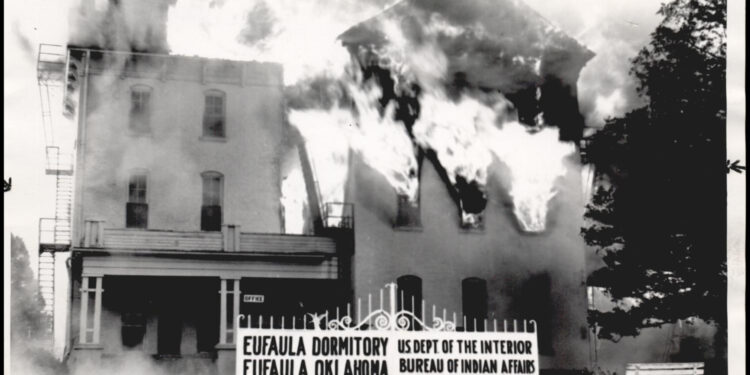

From the 1870s until the 1960s, there were more than 350 taxpayer-funded, often church-run, Native American boarding schools, according to the National Native American Boarding School Coalition.

There were more than 400 federally run or supported Indian schools in the country, with Oklahoma having the highest number of 76 Indian boarding schools; Arizona comes in second with 47.

These may include stories of physical, emotional, mental, and sexual abuse. Identities were stripped of the children, and language and culture were disposed of, even down to hair being cut to short lengths.

Children lived in confinements and unfair punishments, dealing with the forced removal from their families, which some never saw again. Some children never made it home and died at the hands of the federal government without notifying the family of said children. Unfortunately, some were laid to unrest with not even a name of identification.

The investigation also found more than 500 children died while attending these schools, although that number is likely higher.

Haaland claims that being an open ear to these survivors who may be sharing their stories for the first time is an integral part of the healing process. “We understand that sometimes, just getting things off your chest, just being able to say it out loud, means something to them,” Haaland said. “So, I think most of all, we want to make sure we are there to listen.”

Many have shed tears when sharing their testimonies, and Haaland shed many as she tirelessly devoted time and attention to each survivor.

“I’m with you on this journey. I will listen. I will grieve with you. I will weep alongside you.”

Those who want to tell their stories can still do so by emailing roadtohealing@ios.doi.gov.