Byline: Morgan Taylor/Multimedia Producer

Kaylea Berry/Reporter

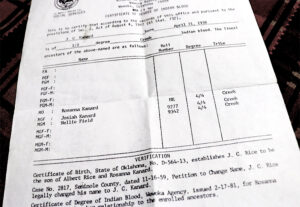

WEWOKA, Oklahoma – The story of J.C. Kanard started in the small rural community of Dustin, located in the southern region of the Mvskoke Reservation, on April 21, 1938. He was born to a full-blood Muscogee (Creek) woman, Rosanna Kanard, the daughter of Nellie Field and Josiah Kanard, who were both certified as full-blood Creeks by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Albert Rice, a non-native, is Kanard’s biological father. According to Kanard, his grandfather “ran Rice off” using a weapon, intimidation, and threats. Rice eventually settled on the West Coast in California. Kanard was well into his 50s before meeting Rice for the first time. Rice died just a few years after they first met.

Kanard’s original birth certificate read J.C. Rice as his legal name. However, in 1959 at 21, Kanard changed his last name to his mother’s maiden name Kanard. He has never known what J.C. stands for.

His mother was married to Mr. William Powell of Holdenville, a non-native who fathered Kanard’s three younger brothers, William Jr., Sandy, Jimmy, and younger sister Bonnie. Each was born between the years 1945-1953. Of his siblings, he is the last one living.

When Kanard was a young boy, he remembers his infant sister being taken from the home by an aunt, Sally Bunny, who ultimately adopted and raised the little girl. His sister, the child of Rosanna Kanard and Edward Scott, went by the name of Lorene Bunny. He did not see her again until they crossed paths at the same school later in life.

Kanard primarily lived with his grandparents in Dustin and occasionally stayed with his mother and stepfather. He would work with his grandparents in the fields.

“I picked cotton when I was three of four years old,” said Kanard. “I think my mother was there sometimes.”

Kanard has few childhood memories of his mother.

“I didn’t have that much of a connection with her,” Kanard said.

He recalls one time staying with his mother and stepfather for a week.

“It was getting dark, and I said where do you want me to sleep,” he said. “She threw me a blanket and said, ‘you sleep under the bed.'”

He can remember being dropped off by his mother and her husband when he was five years old at the Euchee Mission Boarding School over an hour away in Sapulpa, Okla. Euchee was originally a co-educational facility under the direction of the Presbyterian Mission Board, authorized in 1891 and built in 1894.

The school opened in the fall of 1894 with about fifty students. At first, the school had only two dormitories and a three-room schoolhouse on 40 acres of tribal property. The Bureau of Indian Affairs took over operations in 1907.

It became a boy’s school in 1925, and 1929 initiated the integration of older students into the Sapulpa public school system. All remaining students were transferred to the Sapulpa public schools in 1947, when the school was abolished.

Kanard attended the school for first, second, and third grade between 1943 and 1946. When he first arrived, he only spoke the Mvskoke language and did not know English.

From what he can recall, most of what he learned at the school was how to read, write and speak English. During his time at the school, he participated in a Christmas performance and recited John 3:7 from the Bible. Nearly 80 years later and he still remembers it.

“It says, ‘Marvel not that I say unto you; you must be born again,'” Kanard said.

Christianity was not something new for Kanard. He attended Middle Creek #1 Baptist Church in Carson and occasionally Thlewarle Indian Baptist Church in Dustin with his grandparents. Kanard took heart to what John 3:7 says and gave his life to God on Easter Sunday a year later.

With his head down and eyes looking at the ground, he spoke of more memories at Euchee Mission Boarding School.

“Us boys, we’d be playing out on the playground, and you know how kids do; they get carried away,” Kanard said. “We’d get to talking in our native language.”

According to Kanard, the boys were punished for using their native language.

“They’d take us into the basement of the auditorium,” Kanard said. “Pull our britches off, we’d grab the other end of the table, lay across the table, and they’d spank us.”

Kanard said that after the punishment, the kids were told, “We don’t speak the native language around here; you have to speak English.”

Unfortunately, Kanard has no pictures of himself while attending Euchee. The school provided no photos or documents to the students or parents.

At the start of his fourth-grade year, Kanard transferred to Sequoyah Boarding School in Tahlequah. He also completed fifth and sixth grade there.

The only bad time he had at the school had him laughing while telling the story of when he and another boy were playing in poison oak and didn’t know it.

“It wasn’t too bad other than that week I spent at the hospital,” Kanard said. “I guess I was allergic.”

He remembers being bathed in tar each day for relief.

Sequoyah originated in 1871 due to the Cherokee National Council’s intent to house the orphans of the Civil War. The council authorized the Chief of the Cherokee Nation at the time to sell the Cherokee Orphan Training School, including 40 acres of land and all the buildings, to the U.S. Department of Interior for $5,000 in 1914. The name was later changed to Sequoyah Orphan Training School.

It underwent a few name changes, added the seventh and eighth grades, and then became Sequoyah Schools in 2006. Today, Sequoyah Schools enrolls more than 300 students representing 42 tribes and 14 states. Students are eligible to attend if they are members of a federally recognized Indian tribe or one-fourth blood descendants of such members.

After three years at Sequoyah, Kanard’s grandparents decided to keep him home, and he attended Dustin Public Schools.

Due to the lack of documentation, one of his teachers brought him to the principal to determine what grade he should be placed into. He should have been starting seventh grade, but according to Kanard, the principal said to “put him back in third grade. Those Indian schools don’t know how to teach.”.

Kanard said there were just as many Native students at the public schools as at the boarding schools. He did not have issues fitting in and was able to participate in extracurricular activities.

He remembers seeing his sister Lorene while he attended Dustin. “She was just starting school about first or second grade,” he said.

Even though she was just an infant the last time he saw her, he claims he remembered her face.

“I recognized her right off,” Kanard said. “I don’t know if the Lord was telling me who she was or what, but it worked out.”

From that point on, the two were able to stay in contact.

Kanard attended Fairview Public School for the seventh grade but eventually transferred to Chilocco Indian School. He learned carpentry skills while at school. According to Kanard, the students in the carpentry classes reroofed the multi-story dormitory building while attending the school. The siblings reunited again at Chilocco, where Kanard only attended for a year, but Lorene ended up graduating.

“Whatever tore up, we had to fix it,” he said.

He attempted to play football and baseball at Chilocco but did not get to play much.

Kanard finished his high school years at Holdenville Public School, graduating at 21. He enlisted in the military at 16 years old, paid $20 monthly, and worked at the local IGA grocery store, where he earned 50 cents an hour. He did this to provide for himself instead of playing sports, where he faced issues with nepotism.

“Coaches had their picks, and I didn’t get to play,” said Kanard.

He said the bankers, merchants, police, and lawyers’ kids would always get the most playing time even though he practiced as hard as they did.

After graduating high school, he met and married the love of his life, Frida, and they had three children together. She passed away in 2013.

At the age of 85, Kanard buried many memories he carried with him through his childhood. Although during those times, he never felt like he could talk about it, even with his grandparents.

“I didn’t tell them anything about boarding schools,” Kanard said. “They never did ask.”

Still, he holds no grudges over the era and “carries on.”

Kanard said, “I just put it in my mind that it just happened, and I don’t hold anyone responsible or anything like that.”

The stories of boarding school survivors are pertinent to the Native American people’s history. While Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland travels around the country collecting oral stories, Mvskoke Media is determined to gather those of the Mvskoke people specifically. Anyone interested in sharing the story of boarding school impacts is encouraged to contact Mvskoke Media at 918-732-7720.